The Replay is a weekly newsletter for dev and engineering leaders.

Delivered once a week, it's your curated guide to the most important conversations around frontend dev, emerging AI tools, and the state of modern software.

Every day we use a number of different user interfaces (UIs) as we go about our daily lives. I wake up and hit snooze on the clock UI of my iPhone. Five minutes later, I wake up again and check my schedule in Google Calendar, followed by looking through Twitter to get my morning news — all before 7 a.m.

In all the UIs I have used, most of them have one thing in common: they have bugs. The more complex the interface, the more bugs. In the majority of cases, these bugs result in small inconveniences we can work around. However, because these interfaces are used every day, often multiple times per day, these small inconveniences can grow into big frustrations.

Over time, these interfaces are iterated upon, bugs are removed, and we are left with a more pleasant experience. But with time comes new user requirements, the interfaces change, and we are back to square one, with new bugs. We have been making interfaces for as long as there have been computers. How is it that we are still in a situation where there are still so many bugs?

The simple answer is because we are building for humans. Regardless of how well we tailor our design, we can’t predict for certain how a user will interact with our interface.

In the majority of interfaces, there are a number of different paths a user can take. The more powerful the software, the more complex the UI, the more paths.

Some of these paths we can predict and build for; some we can’t. We call these edge cases. Edge cases result in an interface getting into a state that we haven’t predicted, which can lead to unintended behavior.

I believe that edge cases are the main source of UI bugs. I also believe that the source of these edge cases is a development approach that is a poor fit for building UIs: event-driven development.

To explain, let’s look at how a simple UI component is developed using event-driven development.

Our component will have a single button. When clicked, a request for an image is made. If the request is successful, the image is displayed. If the request fails, an error message is displayed. You can test this component out in the sandbox below.

In my experience, this would be a common approach for developing this component.

import React, { useState } from "react";

import { fetchImage } from "./fetchImage";

const ImageFetcher = () => {

const [isFetching, setFetching] = useState(false);

const [isError, setError] = useState(false);

const [isSuccess, setSuccess] = useState(false);

const [image, setImage] = useState(null);

const clickHandler = e => {

setFetching(true);

fetchImage()

.then(response => {

setSuccess(true);

setImage(response);

})

.catch(() => {

setError(true);

})

.finally(() => {

setFetching(false);

});

};

return (

<section>

{isFetching && <p>loading...</p>}

{isSuccess && <img src={image} alt="" />}

{isError && <p>An error occured</p>}

<button onClick={clickHandler}>Get Image</button>

</section>

);

};

We use React and the useState Hook to manage our state, creating multiple boolean flags — one flag for isFetching, isSuccess, and isError. I see two significant disadvantages to this approach:

The component should never be in both the fetching state and the error state at the same time. But with this setup, it’s possible. Our component only has four intended states: the default state, fetching, success, and error.

With this, however, we have eight different combinations. Our component is relatively simple right now. But if we get new requirements and it grows in complexity, we are shooting ourselves in the foot by building on a shaky foundation.

I think code is more readable, stable, and workable when you have a clear separation of concerns. In this example, the state logic is embedded in the UI implementation. The code that is responsible for deciding what should be rendered is entangled with the code that determines how it should be rendered.

This also creates more work if we need to migrate to a different UI library or framework, such as Vue.js or Angular. Whichever one you migrate to, you would want to keep the same state logic. But because it’s entangled, you would need to rewrite it.

Consider a scenario in which we identified a new requirement while testing out this component: we need to account for users who press the button multiple times. These users are making multiple requests and putting needless load on the server. To prevent this from happening, we have added a check in our click handler, which will prevent more than one request being sent.

import React, { useState } from "react";

import { fetchImage } from "./fetchImage";

const ImageFetcher = () => {

const [isFetching, setFetching] = useState(false);

const [isError, setError] = useState(false);

const [isSuccess, setSuccess] = useState(false);

const [image, setImage] = useState(null);

const clickHandler = e => {

if (isFetching) {

return;

}

setFetching(true);

fetchImage()

.then(response => {

setSuccess(true);

setImage(response);

})

.catch(() => {

setError(true);

})

.finally(() => {

setFetching(false);

});

};

return (

<section>

{isFetching && <p>loading...</p>}

{isSuccess && <img src={image} alt="" />}

{isError && <p>An error occured</p>}

<button onClick={clickHandler}>Get Image</button>

</section>

);

};

This illustrates event-driven development. We center our development around events. We first deal with our event (via the click handler), then we check the state to determine the outcome.

As we discover new requirements or edge cases, we start adding logic to our event handler and more states. This, in turn, creates even more edges cases. Eventually, we end up with state explosion, a component that is hard to read and difficult to enhance.

An alternative approach to UI development is state-driven development. This approach puts states first and events second. To me, the core difference is that we go from being on defense to offense.

Instead of the user being able to trigger any event, leaving us scrambling to catch them all and write logic to handle them, we give the user a state containing a group of events. While we’re in this state, the user can trigger any event in this group, but no more. I believe this makes UI code simpler, scalable, and more robust.

XState is a state management library that enables state-driven development through finite-state machines. If we were to remake out component using React with XState, it might look like this:

import { Machine, assign } from "xstate";

import { fetchImage } from "./fetchImage";

export const machine = Machine({

id: "imageFetcher",

initial: "ready",

context: {

image: null

},

states: {

ready: {

on: {

BUTTON_CLICKED: "fetching"

}

},

fetching: {

invoke: {

src: fetchImage,

onDone: {

target: "success",

actions: assign({

image: (_, event) => event.data

})

},

onError: "error"

}

},

success: {},

error: {}

}

});

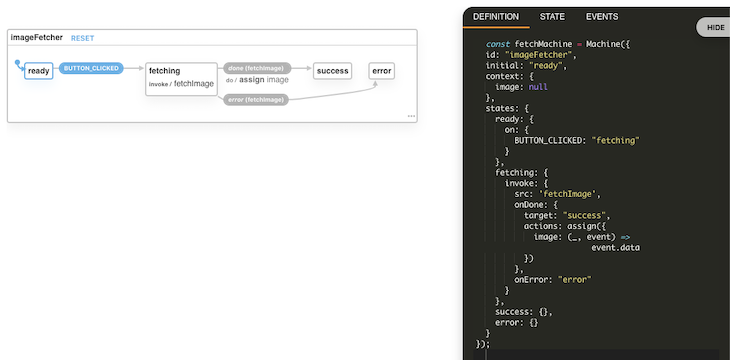

Above we are defining our machine by calling XState’s Machine function and passing in a config. The config is just a JavaScript object. It has a states property, which defines what states our machine can be in.

Here we are defining four states: ready, fetching, success, and error. Our machine can only be in one of these states at a time. Within each state, we define what events can occur while the machine is in that state. If the machine is in the ready state and the BUTTON_CLICKED event occurs, we’ll transition to the fetching state.

Within the fetching state, we have an invoke. When we enter this state, a promise will be called. If the promise resolves, the machine will transition to the success state, and the image will be stored in the machine’s context (a place to store quantitative data). If the promise is rejected, the machine will transition to the error state.

import React from "react";

const ImageFetcher = () => {

const [current, send] = useMachine(machine);

const { image } = current.context;

return (

<section>

{current.matches("ready") && (

<button onClick={() => send("BUTTON_CLICKED")}>

Get Image

</button>

)}

{current.matches("fetching") && <p>loading...</p>}

{current.matches("success") && <img src={image} alt="" />}

{current.matches("error") && <p>An error occured</p>}

</section>

);

};

Above we have our React component. We call XState’s useMachine hook and pass in our machine. This returns two values:

current, a variable we can use to query the machine’s statesend, a function that can send an event to the machineThere are five advantages to this approach:

This makes things significantly easier to understand.

In our previous example, we dealt with our event, then we checked the state to see what the outcome would be. In state-driven development, we swap it around: the first thing we do when an event is triggered is check what state we’re in.

Now, within this state, we check what the event does. Events are scoped to states: if an event is triggered and it’s not defined with the current state, it doesn’t do anything. This gives you more confidence and greater control over what the user is able to do.

All our state logic is independent from the UI implementation. Having a separation of state logic and rendering implementation makes our code more readable and easier to migrate. If we wanted to change from React to Vue, for example, we could copy and paste our machine.

We can use our machine to generate tests. This reduces the amount of mundane tests we would need to write and catches more edges cases. You can read more about it here.

Speaking of readability, we can take this machine config and put it into XState’s visualizer. This will give us a state chart, a diagram of our system. The squares represent the states, and arrows represent events — you don’t even need to be a coder to understand this. It’s also interactive.

Using state-driven development, with or without XState, can make UI code simpler, scalable, and more robust. This creates a better experience for the developer and can change the UI frustrations that people face every day into pleasant experiences.

If you want to learn more about building UI components using React with XState, I have started a guide that breaks down XState’s concepts and how to use finite-state machines with React.

Code for examples:

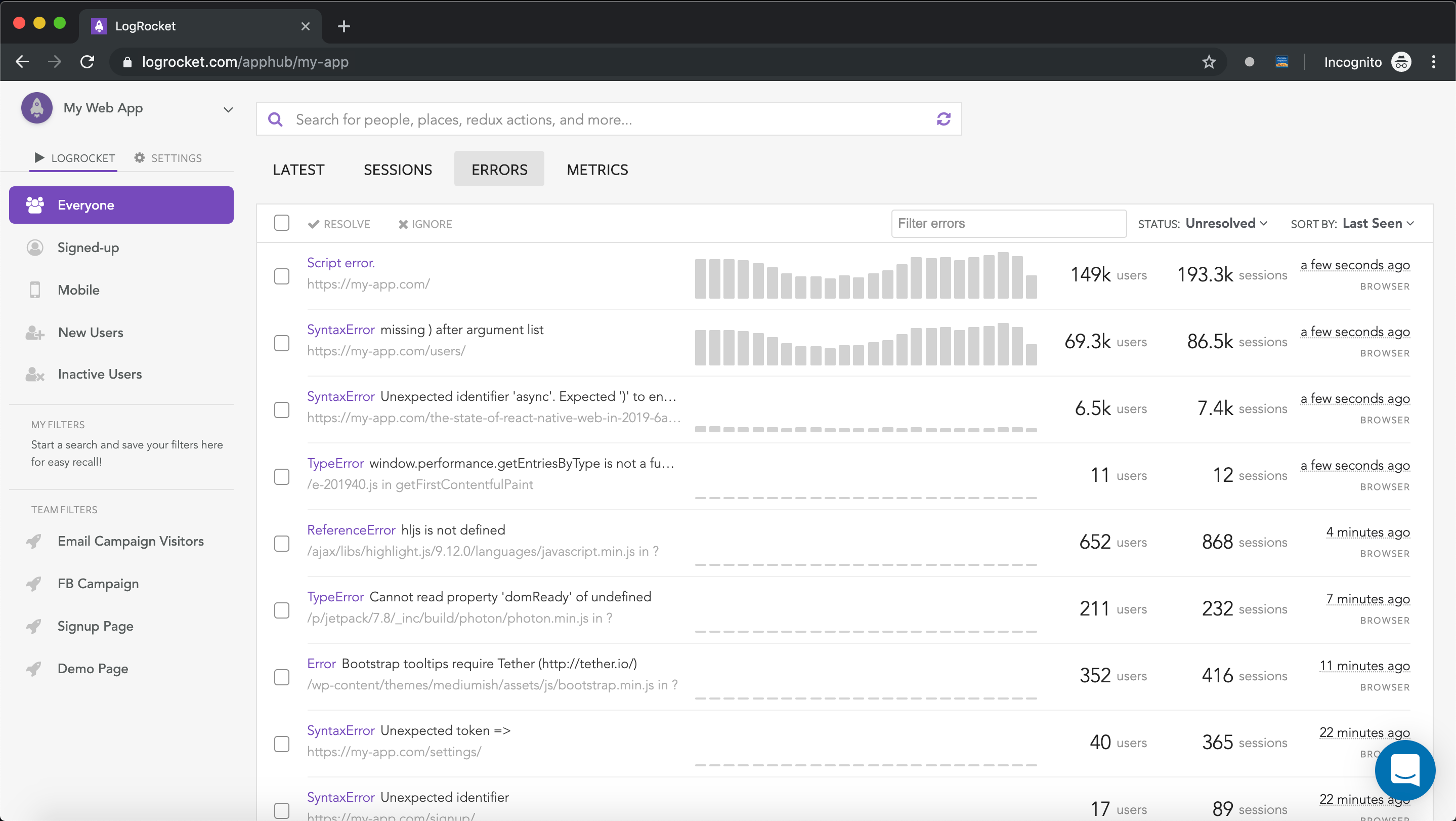

There’s no doubt that frontends are getting more complex. As you add new JavaScript libraries and other dependencies to your app, you’ll need more visibility to ensure your users don’t run into unknown issues.

LogRocket is a frontend application monitoring solution that lets you replay JavaScript errors as if they happened in your own browser so you can react to bugs more effectively.

LogRocket works perfectly with any app, regardless of framework, and has plugins to log additional context from Redux, Vuex, and @ngrx/store. Instead of guessing why problems happen, you can aggregate and report on what state your application was in when an issue occurred. LogRocket also monitors your app’s performance, reporting metrics like client CPU load, client memory usage, and more.

Build confidently — start monitoring for free.

Please note my definition of state-driven development is different than the idea of event-driven programming that you might be familiar with.

Compare the top AI development tools and models of February 2026. View updated rankings, feature breakdowns, and find the best fit for you.

Broken npm packages often fail due to small packaging mistakes. This guide shows how to use Publint to validate exports, entry points, and module formats before publishing.

Discover what’s new in The Replay, LogRocket’s newsletter for dev and engineering leaders, in the February 11th issue.

Cut React LCP from 28s to ~1s with a four-phase framework covering bundle analysis, React optimizations, SSR, and asset/image tuning.

Would you be interested in joining LogRocket's developer community?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now