The Replay is a weekly newsletter for dev and engineering leaders.

Delivered once a week, it's your curated guide to the most important conversations around frontend dev, emerging AI tools, and the state of modern software.

The Cache API provides a mechanism for storing network requests and retrieving their corresponding responses during run-time. It can be used in the absence of an internet connection (or presence of a flaky one) and this makes it integral to the building of progressive web applications (fully optimised web applications that work offline like native applications).

Because it is impossible to predetermine your user-base at development time, it is important to build web services that can be accessed by a broad spectrum of users who may not have the best hardware or may have slow internet connections.

Progressive web applications were created to ensure that web services work on all devices. On mobile devices, they are designed to deliver a user experience that is close to that of native applications. Under the hood, PWAs use service workers to achieve the ideal behavior, and they leverage the Cache API for extra control over network resources.

This Google web fundamentals page describes service workers like this:

A service worker is a script that your browser runs in the background, separate from a web page, opening the door to features that don’t need a web page or user interaction. Today, they already include features like push notifications and background sync. In the future, service workers might support other things like periodic sync or geofencing. A core feature of a service worker is the ability to intercept and handle network requests, including programmatically managing a cache of responses.

We can see that caching can play an important role in the workflow of service workers. This article shows how the Cache API can be used in a service worker, and as a general mechanism of resource storage.

All the code in this tutorial can be found in this repository, feel free to fork it or send in a PR.

In modern browsers, each origin has a cache storage and we can inspect it by opening the browser developer tools:

Pro tip: In Chrome, you can visit

chrome://inspect/#service-workersand click on the “inspect” option (directly under the origin of any already opened tab) to view logging statements for the actions of theservice-worker.jsscript.

The Cache API is available in all modern browsers:

Because older browsers may not support the API, it is good practice to check for its availability before attempting to reference it. The caches property is available on the window object and we can check that it is implemented in the browser with this snippet:

if ('caches' in window){

// you can safely insert your snippet here

}

The Cache API is a great choice for caching URL-addressable resources, that is, you should use the Cache API when you work with network resources that are necessary to load your application. If your application deals with lots of data, you may cache the data that the user will most likely need on page load. These resources may include file-based content, assets, API responses, and web pages.

For the storage of significant amounts of structured data (including files/blobs), you should ideally use the IndexedDB API.

The Cache API ships with several methods to perform the following (CRUD) operations:

Let’s go over some ways to use these methods in our code.

Before we can start storing request-response pairs into our cache storage, we need to create a cache instance. Each origin can have multiple cache objects within its cache storage. We can create a new cache object using the caches.open() method:

const newCache = await caches.open('new-cache');

The snippet above receives the name of the cache as the single parameter and goes on to create the cache with that name. The caches.open() method first checks if a cache with that name already exists. If it doesn’t, it creates it and returns a Promise that resolves with the Cache object.

After the snippet executes, we will now have a new cache object that can be referenced with the name new-cache.

There are three main ways to add items to the cache:

addaddAllputAll of these methods return a Promise, now let’s go over each of these and see how they differ from one another.

The first method, cache.add(), takes a single parameter that can either be a URL string literal or a Request object. A call to thecache.add() method will make a Fetch request to the network and store the response in the associated cache object:

newCache.add('/cats.json')

or to gain more control, we can use a request object:

const options = {

method: "GET",

headers: new Headers({

'Content-Type': 'text/html'

}),

}

newCache.add(new Request('/cats.json', options))

Note: If the fetch is unsuccessful and an error response is returned, nothing is stored in the cache and the

Promiserejects.

This method works similarly to the cache.add() method except that it takes in an array of request URL string literals or Request objects and returns a promise when all the resources have been cached:

const urls = ['pets/cats.json', 'pets/dogs.json']; newCache.addAll(urls);

Note: The promise rejects if one or more items in the array of requests are not cached. Also, while the items in the array are being cached, a new entry overwrites any matching existing entry.

The Cache.put method works quite differently from the rest as it allows an extra layer of control. The put() method takes two parameters, the first can either be a URL string literal or a Request object, the second is a Response either from the network or generated within your code:

// Retrieve cats.json and cache the response

newCache.put('./cats.json')

// Create a new entry for cats.json and store the generated response

newCache.put('/cats.json', new Response('{"james": "kitten", "daniel": "kitten"}'))

// Fetch a response from an external address and create a new entry for cats.json

newCache.put('https://pets/cats.json');

The put method allows an extra layer of control as it lets you store responses that do not depend on CORS or other responses that are dependent on a server response status code.

Pro tip: The first two methods —

add()andaddAll()— are dependent on the state of CORS on the server the data is being requested from. If a CORS check fails, nothing gets cached and thePromiserejects. Usingput(), on the other hand, gives you extra confidence as you can set an in-house response.

After we’ve added some items to the cache, we need to be able to retrieve them during run-time. We can use the match() method to retrieve our cached responses:

// retrieve a new response const request = '/cats.json'; const response = await newCache.match(request);

In the code above, we passed in a request variable to the match method, if the request variable is a URL string, it is converted to a Request object and used as an argument. The match method will return a Promise that resolves to a Response object if a matching entry is found.

The browser uses different factors in determining if two or more Requests match. A Request may have the same URL as another but use a different HTTP method. Two such requests are considered to be different by the browser.

When using the match method, we can also pass an options object as the second parameter. This object has key value pairs that tell match to ignore specific factors when matching a request:

// create an options object

const options = {

ignoreVary: true, // ignore differences in Headers

ignoreMethod: true, // ignore differences in HTTP methods

ignoreSearch: true // ignore differences in query strings

}

// then we pass it in here

const response = await newCache.match(request, options);

In a case where more than one cache item matches, the oldest one is returned. If we intend to retrieve all matching responses, we can use the matchAll() method.

We might not need a cache entry anymore and want it deleted. We can delete a cache entry using the delete() method:

// delete a cache entry const request = '/cats.json'; newCache.delete(request);

In the code above, we saved a URL string in the request variable but we can also pass in a Request object to the delete method. In a case where we have more than one matching entries, we can pass in a similar options Object as we did with the match method.

Finally, we can delete a cache by calling the delete() method on the caches property of the window object. Let’s delete our cache in the snippet below:

// delete an existing cache

caches.delete('new-cache');

Note: When a cache is deleted, the

delete()method returns aPromiseif the cache was actually deleted and a false if something went wrong or the cache doesn’t exist.

In this article, we took a tour of the Cache API and discussed its usefulness to the development of progressive web applications. We also explored its CRUD methods and saw how easily we can retrieve responses and store requests.

Note: For security reasons, a cache is bound to the current origin and other origins cannot access the caches set up for other origins.

All the code in this tutorial can be found in this repository, feel free to fork it or send in a PR.

Debugging code is always a tedious task. But the more you understand your errors, the easier it is to fix them.

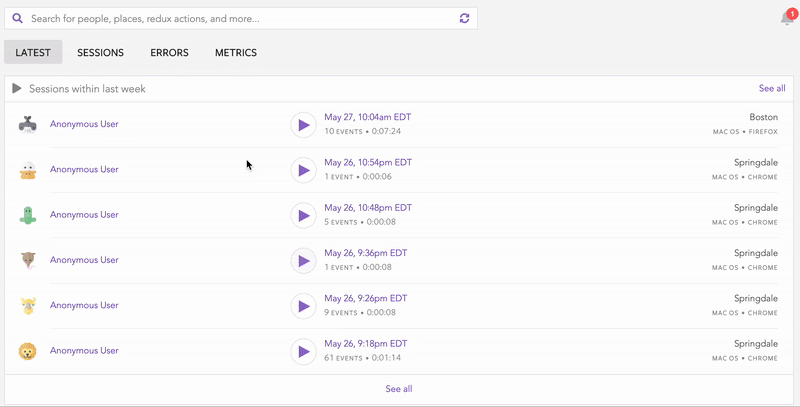

LogRocket allows you to understand these errors in new and unique ways. Our frontend monitoring solution tracks user engagement with your JavaScript frontends to give you the ability to see exactly what the user did that led to an error.

LogRocket records console logs, page load times, stack traces, slow network requests/responses with headers + bodies, browser metadata, and custom logs. Understanding the impact of your JavaScript code will never be easier!

Solve coordination problems in Islands architecture using event-driven patterns instead of localStorage polling.

Signal Forms in Angular 21 replace FormGroup pain and ControlValueAccessor complexity with a cleaner, reactive model built on signals.

Discover what’s new in The Replay, LogRocket’s newsletter for dev and engineering leaders, in the February 25th issue.

Explore how the Universal Commerce Protocol (UCP) allows AI agents to connect with merchants, handle checkout sessions, and securely process payments in real-world e-commerce flows.

Hey there, want to help make our blog better?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now

2 Replies to "Working with the JavaScript Cache API"

One of the best articles on the topic that I have found so far! Well explained topics, and a little bit extra love for the explanations being in vanilla js 😀

Thanks for sharing the best articles on this topic. It’s very helpful to understand these topics😊