Editor’s note: This tutorial was last updated on 01 March 2022 to reflect updated versions of Node.js and Cypress.

Writing large scale applications can very quickly become complex, and the problem is only exacerbated as teams grow and more people work on the same codebase. Therefore, testing is an essential aspect of software engineering, and is arguably even more important in frontend development. With so many moving parts, writing unit and functional tests alone might not be sufficient to verify the application’s correctness.

For example, with a unit test, you can’t really verify that a particular user flow doesn’t cause issues. In this case, end-to-end (E2E) testing comes in handy, allowing you to replicate user behavior on your application and verify that everything is working as it should. If you’re writing production-grade web apps, writing E2E tests is a no-brainer.

In this article, we’ll take a look at how to write useful E2E tests on the frontend using Cypress. While there are other E2E testing tools like Selenium and Nightwatch.js, we’ll focus on Cypress because of its suite of features, which include time traveling through your tests, recording tests for later playback, and more.

To follow along with this tutorial, you’ll need to have recent versions of Node.js and npm installed. You can access the full source code used for this tutorial on GitHub. Let’s get started!

The Replay is a weekly newsletter for dev and engineering leaders.

Delivered once a week, it's your curated guide to the most important conversations around frontend dev, emerging AI tools, and the state of modern software.

To get started, we’ll create a new project and set up Cypress. Initialize a new project by running the following commands:

$ mkdir cypress-tutorial $ cd cypress-tutorial $ npm init -y

Next, install the Cypress package as a development dependency:

$ npm install --save-dev cypress

Open the package.json file in the root of your project and update the scripts property to the following:

"scripts": {

"test": "npx cypress run",

"cypress:open": "npx cypress open"

},

Save and close the file, then in the root folder of your project, create a file called cypress.json, which is the configuration file where you can customize Cypress’ behavior for this specific project. Add the following code to the file and save it:

{ "chromeWebSecurity": false }

We’ll explore the command above in detail later on in the tutorial.

For those of us who follow the Agile methodology, user stories usually follow a format that looks similar to the following:

"When a user takes a specific action, then the user should see this."

To determine how to write an E2E test for that specific story, you’ll simulate taking the action the user is expected to take through the test, then assert that the resulting application state matches your expectations. When testing frontend applications, that process can usually be broken down into the following steps:

We’ll write three tests to assert that we can perform certain actions on Wikipedia by mimicking a user’s actions. For each test, we’ll write a user story before writing the actual test.

Although for the sake of this tutorial, we’re using Cypress on a public website, it’s not meant to be used on websites you don’t own.

Before we begin writing the tests, you need to create a special folder to hold your Cypress tests. In the root of your project, run the following commands:

$ mkdir cypress && cd cypress $ mkdir integration && cd integration

All of our tests will be placed inside the cypress/integration folder, which is where Cypress tries to locate the tests by default. You can change the location for your test files using the integrationFolder configuration option.

When a user visits the homepage, types in the search box, and clicks on the search icon, then the user should see a new page populated with the results from their search term.

The user story for this example is pretty straightforward, simply asserting the correct behavior for a search action on the homepage by a hypothetical user. Let’s write the test for it.

Inside the cypress/integration folder, create a new test file called homepage_search_spec.js and open it in your favorite text editor:

describe('Testing Wikipedia', () => {

it('I can search for content', () => {

cy.visit('https://www.wikipedia.org');

cy.get("input[type='search']").type('Leo Panthera');

cy.get("button[type='submit']").click();

cy.contains('Search results');

cy.contains('Panthera leo leo');

});

});

Let’s go through the test and see how it matches the user story we defined earlier.

A majority of your E2E tests will follow the format above. You don’t need to care about how the app perfoms these actions in the background, instead, all you really need to do is specify the actions that should be performed. The straightforward Cypress syntax makes it easy even for non-programmers to read and understand your tests.

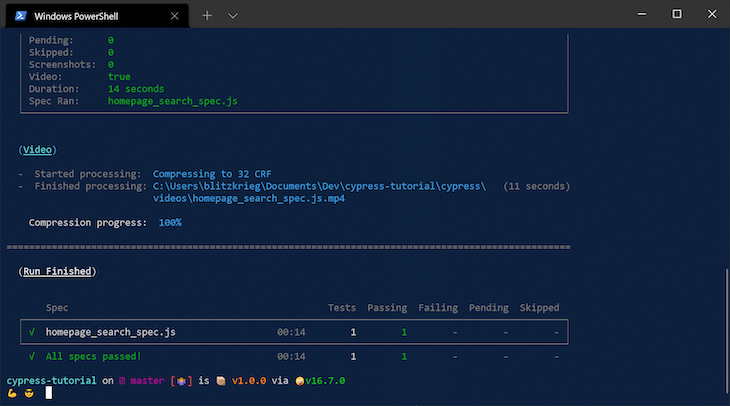

Now, let’s go ahead run the test. Return to your your terminal and run the npm test command. Cypress will look inside the cypress/integration folder and run all the tests there:

Your terminal isn’t the only way to run your tests. Alternately, you can run them in the browser, where you’ll get a real-time view of the testing process as Cypress executes it according to your specifications.

In your terminal, run the command below:

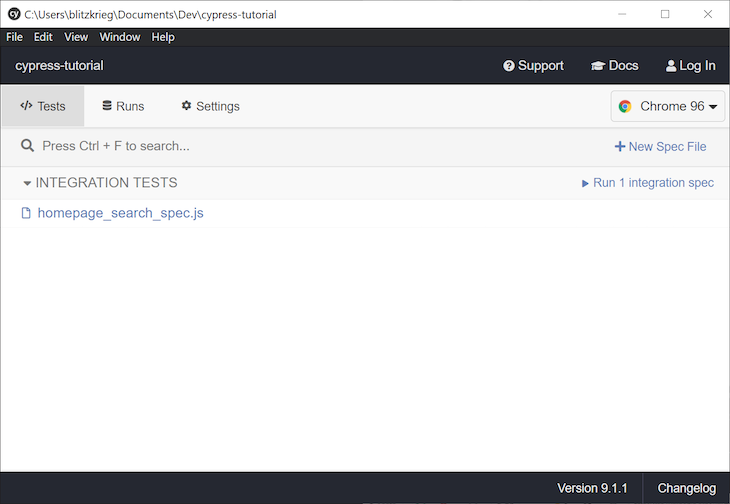

npm run cypress:open

A window should pop up that looks like the image below:

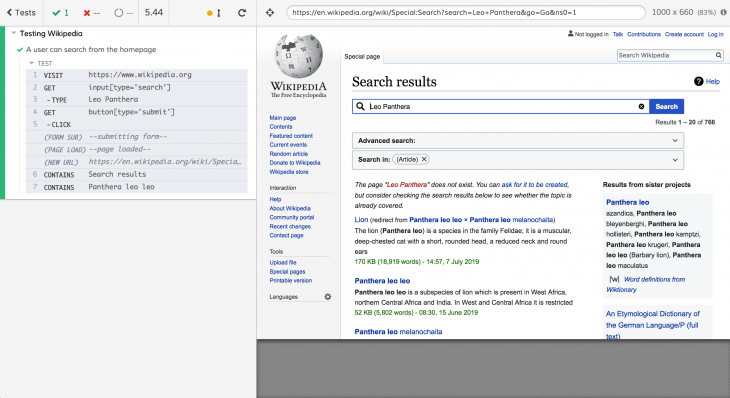

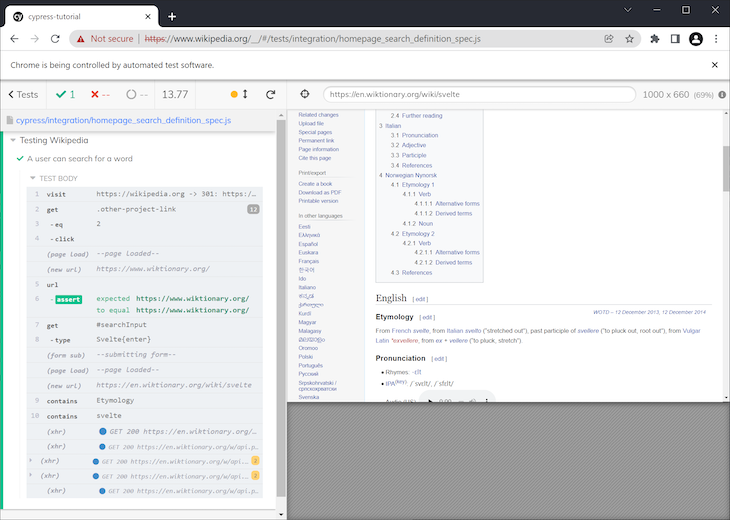

To run your tests, click on the homepage_search_spec.js entry, and you should see another window pop up:

In the top left corner of the window, you can get a quick view of how many passing and failing tests you have in your test suite. The right side of the window displays what a user would see if they interacted with your application according to the way you specified in the test.

With this simple test, we’ve been able to assert that the search functionality on Wikipedia has satisfied our hypothetical user story requirements.

When a user visits the homepage, clicks on the language switcher, and selects a new language, they should be redirected to the appropriate domain for the selected language.

Inside the cypress/integration folder, create a new file called homepage_switch_language_spec.js, open it in your text editor, and add the following code into the file:

describe('Testing Wikipedia', () => {

it('A user can switch languages', () => {

cy.visit('https://wikipedia.org');

cy.contains('Read Wikipedia in your language');

cy.get('#js-lang-list-button').click();

cy.contains('Yorùbá').click();

cy.url().should(

'equal',

'https://yo.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oj%C3%BAew%C3%A9_%C3%80k%E1%BB%8D%CC%81k%E1%BB%8D%CC%81',

);

cy.contains('Ẹ kú àbọ̀');

});

});

Let’s talk about some Cypress-specific syntax. On line three, we’ve instructed Cypress to visit Wikipedia’s homepage. On line four, we assert that we’re on the page we want to be by confirming that the page contains the text Read Wikipedia in your language.

On line five, we query the language switcher button by its ID and simulate a click action on it. You can find out the element’s ID by inspecting it in Chrome Developer Tools. This brings me to an important concept in writing Cypress tests; there are multiple ways to select a DOM element on Cypress, for example, by targeting its ID, class, or even its tag type.

In this particular test, we’re targeting the button’s ID, but in our previous test, we targeted the tag name and attribute. Be sure to check out the official Cypress docs to explore the different ways of selecting a DOM element.

On line six, we encounter another common Cypress command, which you’ll notice shows up a lot in tests. We assert that there’s an element with the text Yorùbá on the DOM, then we simulate a click on it.

This action will cause Wikipedia to redirect you to the appropriate domain for the language you selected. In our case, we selected the Yorùbá language from West Africa, and we can confirm that we were redirected to the correct page by looking at the current page’s URL.

On line seven, we do exactly that. By calling cy.url(), we get the URL of the current page as text, then we assert that it should equal the appropriate domain for the Yorùbá language. On line eight, we have an extra optional check to see if there is any content on the page in the Yorùbá language.

Bonus fact: Ẹ kú àbọ̀ means “Welcome” in the Yorùbá language and is pronounced Eh – Koo – AhBuh.

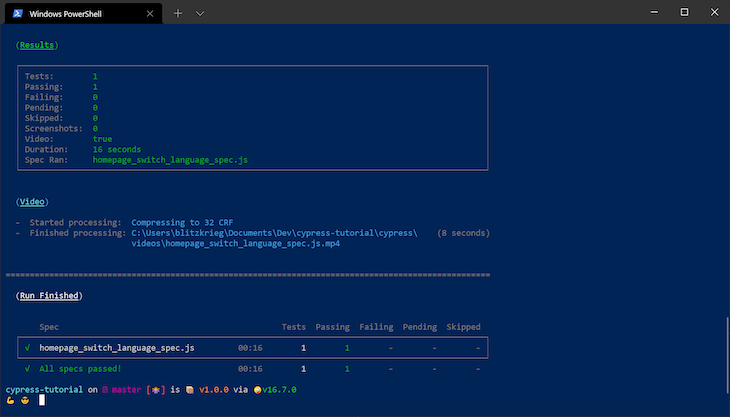

When you run the test using the command below, it should pass. Instead of running all tests, as demonstrated earlier, the --spec option is used to run a specific Cypress test:

$ npm test -- --spec .\cypress\integration\homepage_switch_language_spec.js

When a user visits the homepage and clicks on the link to Wiktionary, then the user should be redirected to wiktionary.org. When a user on wiktionary.org searches for a definition by typing in the search bar and hitting enter, the user should be redirected to a page with the definition of that search term.

Let’s review another straightforward user story. For example, let’s say we want to check for the definition of the word “svelte” on Wiktionary. Before searching for the word, we’ll start off on Wikipedia’s homepage and navigate to Wiktionary .

Inside the cypress/integration folder, create a new file named homepage_search_definition_spec.js, open it, and paste in the code below:

describe('Testing Wikipedia', () => {

it('A user can search for a word', () => {

cy.visit('https://wikipedia.org');

cy.get('.other-project-link')

.eq(2)

.click();

cy.url().should('equal', 'https://www.wiktionary.org/');

cy.get('#searchInput').type('Svelte{enter}');

cy.contains('Etymology');

cy.contains('svelte');

});

});

Let’s walk through this test as we did the one before. On line three, we visit Wikipedia’s homepage as usual. On line four, we target a class name, pick the third element with the class, and simulate a click on the element. Don’t forget that indices start at 0.

Before we move further, you should beware of a little caveat; if your code relies on auto-generated CSS classes, targeting elements by class names might result in inconsistent test results. In those cases, targeting by ID or tag type and attribute would be the way to go.

On line seven, we assert that we’re on the correct domain by checking the URL using cy.url(). Another caveat to keep in mind; if you’re testing your own app, the need to navigate to another domain may be rare. For this reason, this test would fail if we didn’t add "chromeWebSecurity": false in our cypress.json config.

On line eight, we target the search input by its ID. Then, we simulate a change event by typing in “svelte” and hitting the enter button, handled by {enter}. This action takes us to a new page with the result of our query.

On lines nine and ten, we confirm that we’re on the correct page by asserting that the words “etymology” and “svelte” can be found on the page. Run the test using either the command below or the browser to see you newfound skill:

$ npm test -- --spec .\cypress\integration\homepage_search_definition_spec.js

In this tutorial, you’ve seen just how easy it is to verify the correctness of your web app by writing E2E tests using Cypress.

Keep in mind that we’ve barely scratched the surface of what Cypress can do and some of the features it provides. For example, you can even see screenshots of your tests and watch recorded videos by looking under cypress/videos. You can define custom commands to avoid code repetition, mock API response data using fixtures, and more.

Well-written end-to-end tests can save you hours of development time, helping you catch bugs and unexpected behaviors before you merge into production.

Get started by going through the Cypress docs and playing around until you get comfortable enough to start writing live tests. I hope you enjoyed this article, and happy coding!

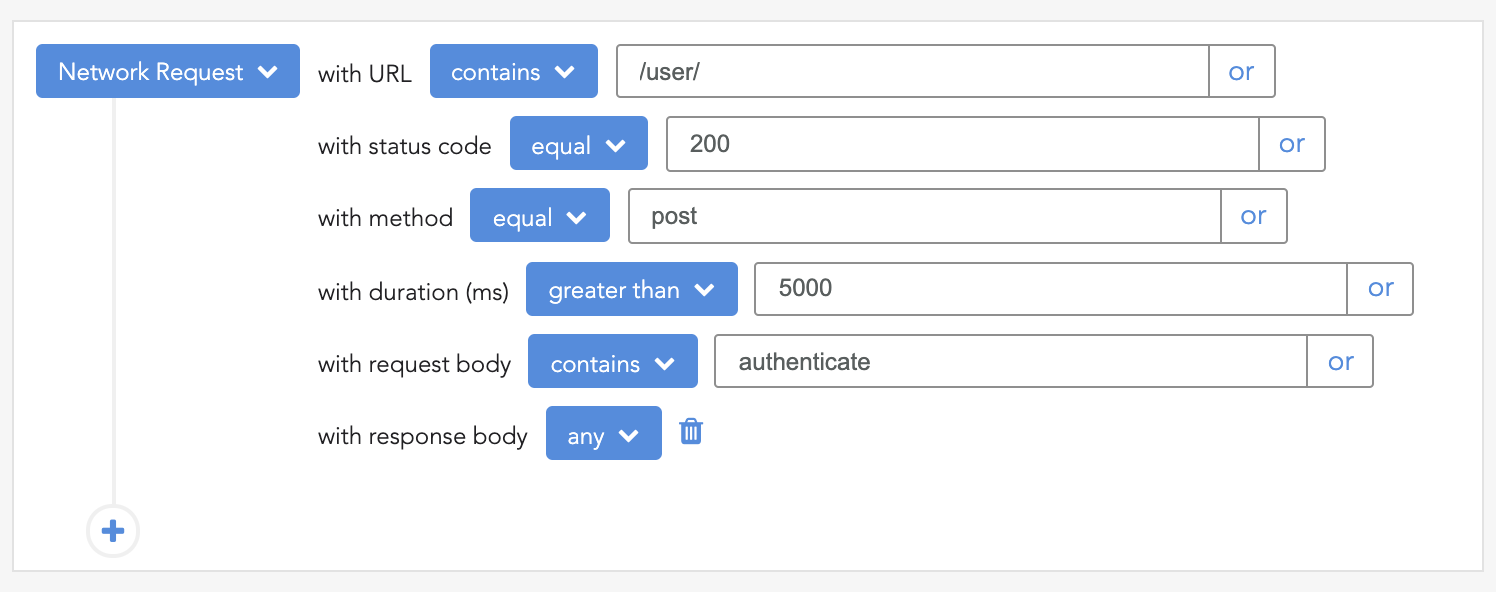

Monitor failed and slow network requests in production

Monitor failed and slow network requests in productionDeploying a Node-based web app or website is the easy part. Making sure your Node instance continues to serve resources to your app is where things get tougher. If you’re interested in ensuring requests to the backend or third-party services are successful, try LogRocket.

LogRocket lets you replay user sessions, eliminating guesswork around why bugs happen by showing exactly what users experienced. It captures console logs, errors, network requests, and pixel-perfect DOM recordings — compatible with all frameworks.

LogRocket's Galileo AI watches sessions for you, instantly identifying and explaining user struggles with automated monitoring of your entire product experience.

LogRocket instruments your app to record baseline performance timings such as page load time, time to first byte, slow network requests, and also logs Redux, NgRx, and Vuex actions/state. Start monitoring for free.

Install LogRocket via npm or script tag. LogRocket.init() must be called client-side, not

server-side

$ npm i --save logrocket

// Code:

import LogRocket from 'logrocket';

LogRocket.init('app/id');

// Add to your HTML:

<script src="https://cdn.lr-ingest.com/LogRocket.min.js"></script>

<script>window.LogRocket && window.LogRocket.init('app/id');</script>

Discover what’s new in The Replay, LogRocket’s newsletter for dev and engineering leaders, in the March 11th issue.

Buying AI tools isn’t enough. Engineering teams need AI literacy programs to unlock real productivity gains and avoid uneven adoption.

If your AI app or agent works perfectly in development but falls apart in production, you’re not alone. In a […]

Compare ESLint and Oxlint, benchmark real speed gains, and learn when migrating to Oxlint makes sense for modern JavaScript teams.

Hey there, want to help make our blog better?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now

4 Replies to "How to write end-to-end tests with Cypress and Node.js"

One comment on your test. You are using cy.contains() and not cy.should()

cy.contains is a selector and not a validator, sure your test will fail if it cannot find the element but its not an assertion.

I can confirm it does fail with contains

While cy.contains() is not a native validator, many commands have a built in assertion that will cause the test to fail if something is not what you expect and cy.contains() is one of them.

In the test cases above, contains() is basically asserting that these texts exist in the DOM which is in itself an assertion. You can check here for more information: https://docs.cypress.io/guides/core-concepts/introduction-to-cypress.html#When-To-Assert

Hi, Can you provide some example for reading the date from a json, csv file and use in the test