Welcome back to another installment of design patterns in Node.js, this is part two but if you want to review part one, where I covered the IIFE, Factory Method, Singleton, Observer and the Chain of Responsibility patterns, feel free to check it out, I’ll be here waiting.

But if you’re not interested or maybe already know about them, keep reading, since I’ll be covering four more patterns today.

I’ll try to provide as many real-life use cases as possible and keep the theoretical shenanigans to a minimum (there is always Wikipedia for that).

Let’s have some fun reviewing patterns, shall we?

The module pattern is definitely one of the most common ones because it seems to have been born out of the necessity for control over what to share and what to hide from your modules.

Let me explain. A very common practice in Node.js (and JavaScript in general), is to organize your code into modules (i.e set of functions that are related to each other, so you group them into a single file and export them out). By default, Node’s modules allow you to pick what to share and what to hide, so no problem there.

But if you’re either using plain old JavaScript or maybe have several modules inside the same file, this pattern helps you hide parts while, at the same time, letting you choose what to share.

This module is heavily dependent on the IIFE pattern, so if you’re not sure how that one works, check out my previous article.

The way you create a module is by creating a IIFE, like this:

const myLogger = ( _ => {

const FILE_PATH = "./logfile.log"

const fs = require("fs")

const os = require("os")

function writeLog(txt) {

fs.appendFile(FILE_PATH, txt + os.EOL, err => {

if(err) console.error(err)

})

}

function info(txt) {

writeLog("[INFO]: " + txt)

}

function error(txt) {

writeLog("[ERROR]: " + txt)

}

return {

info,

error

}

})()

myLogger.info("Hey there! This is an info message!")

myLogger.error("Damn, something happened!")

Now, with the above code, you’re literally simulating a module that is exporting only the info and error functions (of course, that is if you were using Node.js).

The code sample is quite simple, but you still get the point, you can get a similar result by creating a class, yes, but you’re losing the ability to hide methods such as writeLog or even the constants I used here.

This is a very straightforward pattern, so the code speaks for itself. That being said, I can cover some of the direct benefits of using this pattern in your code.

By using the module pattern, you’re making sure global variables, constants or functions that your exported functions require, will not be available for all user code. And by user code, I mean any code that’ll be making use of your module.

This helps you keep things organized, avoid naming conflicts or even user code affecting the behavior of your functions by modifying any possible global variable you might have.

Disclaimer: I do not condone nor am I saying global variables are a good coding standard or something you should even be attempting to do, but considering you’re encapsulating them inside your module’s scope, they’re not global anymore. So make sure you think twice before using this pattern, but also consider the benefits provided by it!

Let me explain this one. If you happen to be using several external libraries (especially when you’re working with plain JavaScript for your browser) they might be exporting their code into the same variable (name collision). So if you don’t use the module pattern like I’m going to show you, you might run into some unwanted behavior.

Have you ever used jQuery? Remember how once you include it into your code, besides the jQuery object, you also have available the $ variable at the global scope? Well, there were a few other libraries doing the same back in the day. So if you wanted your code to work with jQuery by using the $ anyways, you’d have to do something like this:

( $ => {

var hiddenBox = $( "#banner-message" );

$( "#button-container button" ).on( "click", function( event ) {

hiddenBox.show();

});

})(jQuery);

That way, your module, is safe and has no risk of running into a naming collision if included in other codebases that already make use of the $ variable. And this last bit is the most important, if you’re developing code that will be used by others, you need to make sure it’ll be compatible, so using the module pattern allows you to clean up the namespace and avoid name collisions.

The adapter pattern is another very simple, yet powerful one. Essentially it helps you adapt one API (and by API here I mean the set of methods a particular object has) into another.

By that I mean the adapter is basically a wrapper around a particular class or object, which provides a different API and utilizes the object’s original one in the background.

Assuming a logger class that looks like this:

const fs = require("fs")

class OldLogger {

constructor(fname) {

this.file_name = fname

}

info(text) {

fs.appendFile(this.file_name, `[INFO] ${text}`, err => {

if(err) console.error(err)

})

}

error(text) {

fs.appendFile(this.file_name, `[ERROR] ${text}`, err => {

if(err) console.error(err)

})

}

}

You already have your code using it, like this:

let myLogger = new OldLogger("./file.log")

myLogger.info("Log message!")

If suddenly, the logger changes its API to be:

class NewLogger {

constructor(fname) {

this.file_name = fname

}

writeLog(level, text) {

fs.appendFile(this.file_name, `[${level}] ${text}`, err => {

if(err) console.error(err)

})

}

}

Then, your code will stop working, unless, of course, you create an adapter for your logger, like so:

class LoggerAdapter {

constructor(fname) {

super(fname)

}

info(txt) {

this.writeLog("INFO", txt)

}

error(txt) {

this.writeLog("ERROR", txt)

}

}

And with that, you created an adapter (or wrapper) for your new logger that no longer complies with the older API.

This pattern is quite simple, yet the use cases I’ll mention are quite powerful in the sense that they work towards helping with isolating code modifications and mitigating possible problems.

On one side, you can use it to provide extra compatibility for an existing module, by providing an adapter for it.

Case in point, the package request-promise-native provides an adapter for the request package allowing you to use a promise-based API instead of the default one provided by request.

So with the promise adapter, you can do the following:

const request = require("request")

const rp = require("request-promise-native")

request //default API for request

.get('http://www.google.com/', function(err, response, body) {

console.log("[CALLBACK]", body.length, "bytes")

})

rp("http://www.google.com") //promise based API

.then( resp => {

console.log("[PROMISE]", resp.length, "bytes")

})

On the other hand, you can also use the adapter pattern to wrap a component you already know might change its API in the future and write code that works with your adapter’s API. This will help you avoid future problems if your component either changes APIs or has to be replaced altogether.

One example of this would be a storage component, you can write one that wraps around your MySQL driver, and provides generic storage methods. If in the future, you need to change your MySQL database for an AWS RDS, you can simply re-write the adapter, use that module instead of the old driver, and the rest of your code can remain unaffected.

The decorator pattern is definitely one of my top five favorite design patterns because it helps extend the functionality of an object in a very elegant way. This pattern is used to dynamically extend or even change the behavior of an object during run-time. The effect might seem a lot like class inheritance, but this pattern allows you to switch between behaviors during the same execution, which is something inheritance does not.

This is such an interesting and useful pattern that there is a formal proposal to incorporate it into the language. If you’d like to read about it, you can find it here.

Thanks to JavaScript’s flexible syntax and parsing rules, we can implement this pattern quite easily. Essentially all we have to do is create a decorator function that receives an object and returns the decorated version, with either of the new methods and properties or changed ones.

For example:

class IceCream {

constructor(flavor) {

this.flavor = flavor

}

describe() {

console.log("Normal ice cream,", this.flavor, " flavored")

}

}

function decorateWith(object, decoration) {

object.decoration = decoration

let oldDescr = object.describe //saving the reference to the method so we can use it later

object.describe = function() {

oldDescr.apply(object)

console.log("With extra", this.decoration)

}

return object

}

let oIce = new IceCream("vanilla") //A normal vanilla flavored ice cream...

oIce.describe()

let vanillaWithNuts = decorateWith(oIce, "nuts") //... and now we add some nuts on top of it

vanillaWithNuts.describe()

As you can see, the example is quite literally decorating an object (in this case, our vanilla ice cream). The decorator, in this case, is adding one attribute and overriding a method, notice how we’re still calling the original version of the method, thanks to the fact that we save the reference to it before doing the overwrite.

We could’ve also added extra methods to it just as easily.

In practice, the whole point of this pattern is to encapsulate new behavior into different functions or extra classes that will decorate your original object. That would give you the ability to individually add extra ones with minimum effort or change existing ones without having to affect your related code everywhere.

With that being said, the following example tries to show exactly that with the idea of a pizza company’s back-end, trying to calculate the price of an individual pizza which can have a different price based on the toppings added to it:

class Pizza {

constructor() {

this.base_price = 10

}

calculatePrice() {

return this.base_price

}

}

function addTopping(pizza, topping, price) {

let prevMethod = pizza.calculatePrice

pizza.toppings = [...(pizza.toppings || []), topping]

pizza.calculatePrice = function() {

return price + prevMethod.apply(pizza)

}

return pizza

}

let oPizza = new Pizza()

oPizza = addTopping(

addTopping(

oPizza, "muzzarella", 10

), "anana", 100

)

console.log("Toppings: ", oPizza.toppings.join(", "))

console.log("Total price: ", oPizza.calculatePrice())

We’re doing something similar to the previous example here, but with a more realistic approach. Every call to addTopping would be made from the front-end into your back-end somehow, and because of the way we’re adding extra toppings, we’re chaining the calls to the calculatePrice all the way up to the original method which simply returns the original price of the pizza.

And thinking of an even more relevant example — text formatting. Here I’m formatting text in my bash console, but you could be implementing this for all your UI formatting, adding components that have small variations and other similar cases.

const chalk = require("chalk")

class Text {

constructor(txt) {

this.string = txt

}

toString() {

return this.string

}

}

function bold(text) {

let oldToString = text.toString

text.toString = function() {

return chalk.bold(oldToString.apply(text))

}

return text

}

function underlined(text) {

let oldToString = text.toString

text.toString = function() {

return chalk.underline(oldToString.apply(text))

}

return text

}

function color(text, color) {

let oldToString = text.toString

text.toString = function() {

if(typeof chalk[color] == "function") {

return chalk\[color\](oldToString.apply(text))

}

}

return text

}

console.log(bold(color(new Text("This is Red and bold"), "red")).toString())

console.log(color(new Text("This is blue"), "blue").toString())

console.log(underlined(bold(color(new Text("This is blue, underlined and bold"), "blue"))).toString())

Chalk, by the way, is a small little useful library to format text on the terminal. For this example, I created three different decorators that you can use just like the toppings by composing the end result from their individual calls.

The output from the above code being:

Finally, the last pattern I’ll review today is my favorite pattern — the command pattern. This little fellow allows you to encapsulate complex behavior inside a single module (or class mind you) which can be used by an outsider with a very simple API.

The main benefit of this pattern is that by having the business logic split into individual command classes, all with the same API, you can do things like adding new ones or modifying existing code with minimum effect to the rest of your project.

Implementing this pattern is quite simple, all you have to remember is to have a common API for your commands. Sadly, since JavaScript doesn’t have the concept of Interface , we can’t use that construct to help us here.

class BaseCommand {

constructor(opts) {

if(!opts) {

throw new Error("Missing options object")

}

}

run() {

throw new Error("Method not implemented")

}

}

class LogCommand extends BaseCommand{

constructor(opts) {

super(opts)

this.msg = opts.msg,

this.level = opts.level

}

run() {

console.log("Log(", this.level, "): ", this.msg)

}

}

class WelcomeCommand extends BaseCommand {

constructor(opts) {

super(opts)

this.username = opts.usr

}

run() {

console.log("Hello ", this.username, " welcome to the world!")

}

}

let commands = [

new WelcomeCommand({usr: "Fernando"}),

new WelcomeCommand({usr: "reader"}),

new LogCommand({

msg: "This is a log message, careful now...",

level: "info"

}),

new LogCommand({

msg: "Something went terribly wrong! We're doomed!",

level: "error"

})

]

commands.forEach( c => {

c.run()

})

The example showcases the ability to create different commands which have a very basic run method, which is where you would put the complex business logic. Notice how I used inheritance to try and force the implementation of some of the methods required.

This pattern is amazingly flexible and, if you play your cards right, can provide a great amount of scalability for your code.

I particularly like to use it in conjunction with the require-dir module because it can require every module in a folder, so you can keep a command-specific folder, naming each file after the command. This module will require them all in a single line of code and returns a single object with the keys being the filenames (i.e the commands names). This, in turn, allows you to keep adding commands without having to add any code, simply create the file and throw it into the folder, your code will require it and use it automatically.

The standard API will ensure you’re calling the right methods, so again, nothing to change there. Something like this would help you get there:

function executeCommand(commandId) {

let commands = require-dir("./commands")

if(commands[commandId]) {

commands[commandId].run()

} else {

throw new Error("Invalid command!")

}

}

With that simple function, you’re free to keep growing your library of commands without having to change anything! It’s the magic of a well-designed architecture!

In practice, this pattern is great for things like:

The list can keep going since you can pretty much implement anything that is reactive to some form of input into a command-based approach. But the point here is the huge value added by implementing that logic (whatever it is for you). This way you gain amazing flexibility and ability to scale or re-factor with minimum effect on the rest of the code.

I hope this helped shed some light on these four new patterns, their implementations, and use cases. Understanding when to use them and, most importantly, why you should use them helps you gain their benefits and improve the quality of your code.

If you have any questions or comments about the code I showed, please leave a message down in the comments!

Otherwise, see you on the next one!

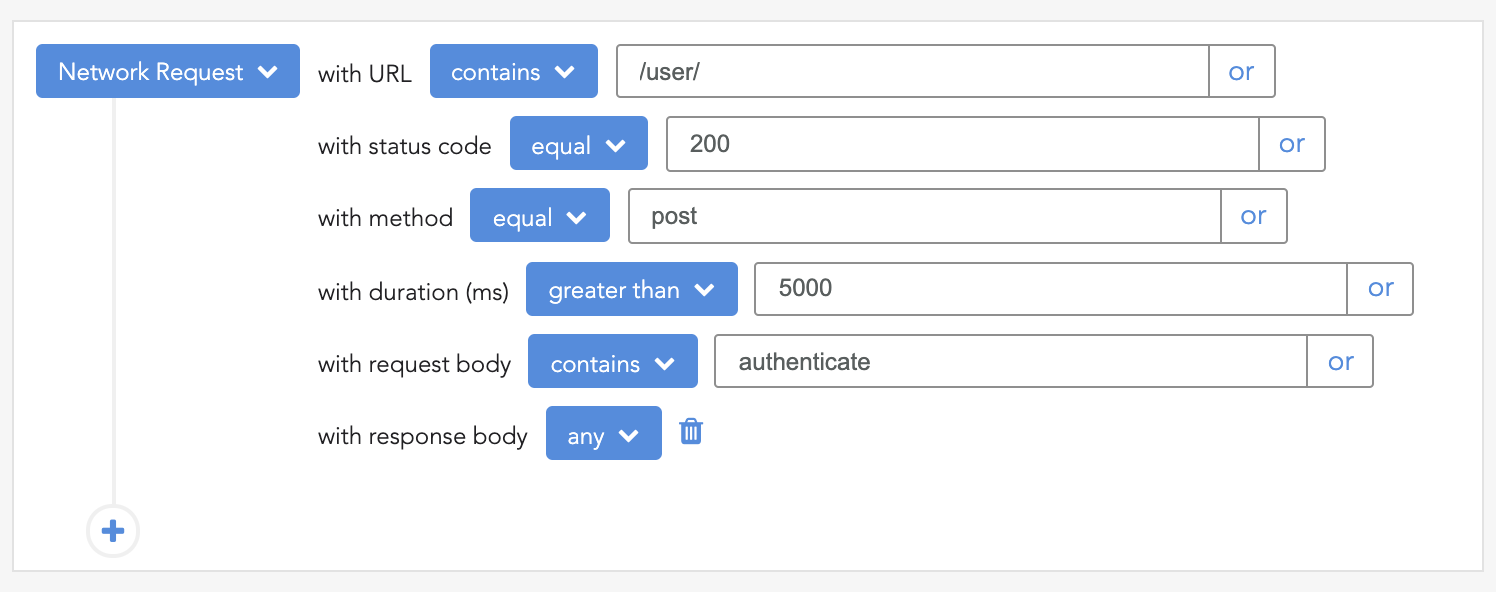

Monitor failed and slow network requests in production

Monitor failed and slow network requests in productionDeploying a Node-based web app or website is the easy part. Making sure your Node instance continues to serve resources to your app is where things get tougher. If you’re interested in ensuring requests to the backend or third-party services are successful, try LogRocket.

LogRocket lets you replay user sessions, eliminating guesswork around why bugs happen by showing exactly what users experienced. It captures console logs, errors, network requests, and pixel-perfect DOM recordings — compatible with all frameworks.

LogRocket's Galileo AI watches sessions for you, instantly identifying and explaining user struggles with automated monitoring of your entire product experience.

LogRocket instruments your app to record baseline performance timings such as page load time, time to first byte, slow network requests, and also logs Redux, NgRx, and Vuex actions/state. Start monitoring for free.

Hey there, want to help make our blog better?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now

Discover how to use Gemini CLI, Google’s new open-source AI agent that brings Gemini directly to your terminal.

This article explores several proven patterns for writing safer, cleaner, and more readable code in React and TypeScript.

A breakdown of the wrapper and container CSS classes, how they’re used in real-world code, and when it makes sense to use one over the other.

This guide walks you through creating a web UI for an AI agent that browses, clicks, and extracts info from websites powered by Stagehand and Gemini.

2 Replies to "Design patterns in Node.js: Part 2"

Do you use Nodejs in your work for production use

Great article, thanks!

A small note related to Adapter pattern: looks like you forgot to add “extends” here:

class LoggerAdapter extends OldLogger{

… }