Node.js is a single-threaded, non-blocking, event-driven JavaScript runtime environment. The Node runtime environment enables you to run JavaScript outside the browser on the server side.

The asynchronous and non-blocking feature of Node.js is primarily orchestrated by the event loop. In this article, you will learn the Node.js event loop so that you can leverage its asynchronous APIs to build efficient Node.js applications. Knowing how the event loop works internally will not only help you write robust and performant Node.js code, but it will also teach you to debug performance issues effectively.

Jump ahead:

The Replay is a weekly newsletter for dev and engineering leaders.

Delivered once a week, it's your curated guide to the most important conversations around frontend dev, emerging AI tools, and the state of modern software.

The Node.js event loop is a continuously running, semi-infinite loop. It runs for as long as there is a pending asynchronous operation. Starting a Node.js process using the node command executes your JavaScript code and initializes the event loop. If Node.js encounters an asynchronous operation such as timers, files, and network I/O while executing a script, it offloads the operation to the native system or the thread pool.

Most I/O operations, such as reading and writing to file, file encryption and decryption, and networking, are time-consuming and computationally expensive. Therefore, to avoid blocking the main thread, Node.js offloads these operations to the native system. There, the Node process is running, so the system handles these operations in parallel.

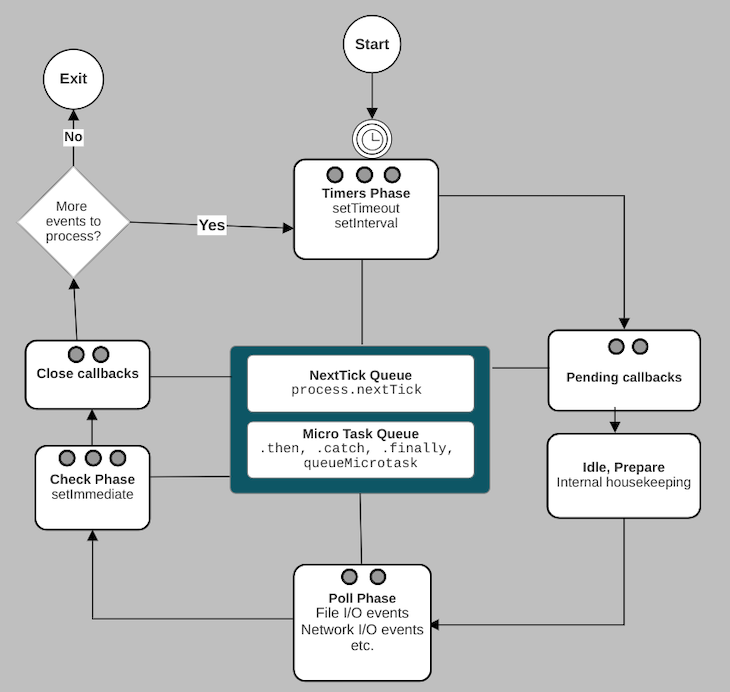

Most modern operating system kernels are multi-threaded by design. Therefore, an operating system can handle multiple operations concurrently and notifies Node.js when those operations are complete. The event loop is responsible for executing your asynchronous API callbacks. It has six major phases:

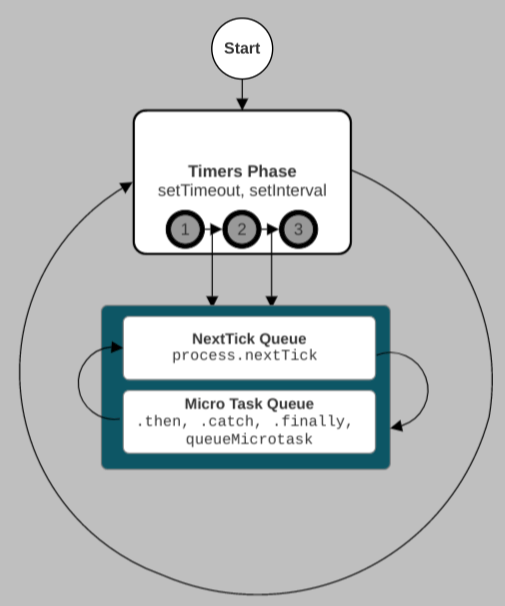

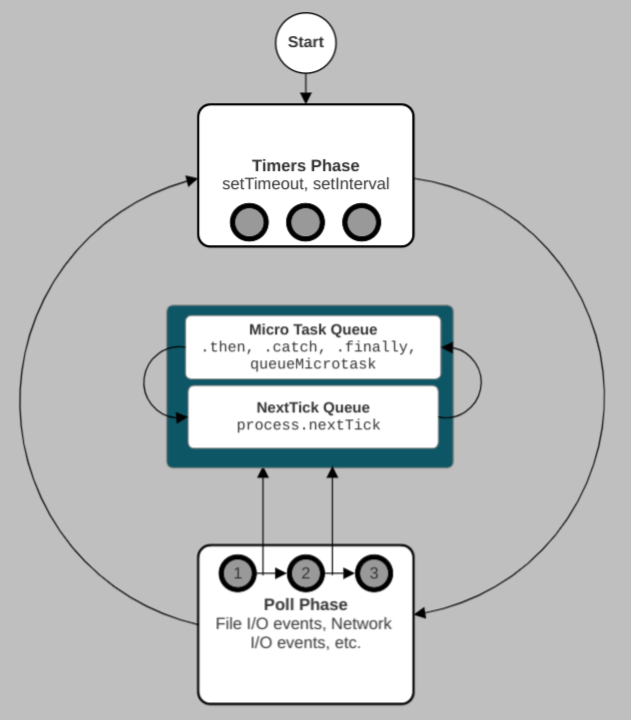

setTimeout and setIntervalsetImmediate callbacksThough the above list is linear, the event loop is cyclical and iterative, as in the diagram below:

After the event loop’s last phase, the next iteration of the event loop starts if there are still pending events or asynchronous operations. Otherwise, it exits, and the Node.js process ends.

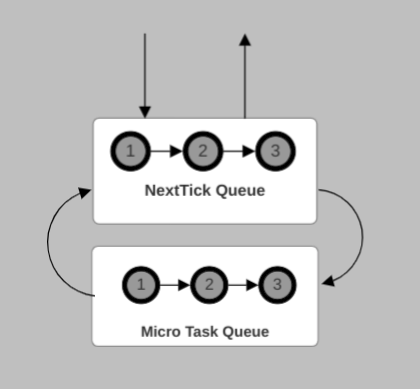

We will explore each phase of the event loop in detail in the following sections. Before that, let’s explore the “next tick” and microtask queues that appear at the center of the event loop in the above diagram. Technically, they are not part of the event loop.

Promises, queueMicrotask, and process.nextTick are all part of the asynchronous API in Node.js. When promises settle, queueMicrotask and the .then, .catch, and .finally callbacks are added to the microtask queue.

On the other hand, the process.nextTick callbacks belong to the “next tick” queue. Let’s use the example below to illustrate how the microtask and the “next tick” queues are processed:

setTimeout(() => {

console.log("setTimeout 1");

Promise.resolve("Promise 1").then(console.log);

Promise.reject("Promise 2").catch(console.log);

queueMicrotask(() => console.log("queueMicrotask 1"));

process.nextTick(console.log, "nextTick 1");

}, 0);

setTimeout(console.log, 0, "setTimeout 2");

setTimeout(console.log, 0, "setTimeout 3");

Let’s assume the three timers above expire at the same time. When the event loop enters the timers phase, it will add the expired timers to the timers callback queue and execute them from the first to the last:

In our example code above, when executing the first callback in the timers queue, the .then, .catch, and queueMicrotask callbacks are added to the microtask queue. Similarly, the process.nextTick callback is added to a queue that we will refer to as the “next tick” queue. Be aware, console.log is synchronous.

When the first callback from the timers queue returns, the “next tick” queue is processed. If more “next ticks” are generated while processing callbacks in the “next tick” queue, they are added to the back of the “next tick” queue and executed as well.

When the “next tick” queue is empty, the microtask queue is processed next. If the microtasks generate more microtasks, they are also added to the back of the microtask queue and executed.

When both the “next tick” queue and microtask queue are empty, the event loop executes the second callback in the timers queue. The same process continues until the timers queue is empty:

The process described above is not limited to the timers phase. The “next tick” queue and the microtask queue are processed similarly when the event loop executes JavaScript in all the other major phases.

As explained above, the Node.js event loop is a semi-infinite loop with six major phases. It has more phases, but the event loop uses some of the phases for housekeeping internally. They have no direct effect on the code you write. Therefore, we won’t cover them here.

Each major phase in the event loop has a first-in-first-out queue of callbacks. For example, the operating system will run scheduled timers until they expire. After that, the expired timers are added to the timers callback queue.

The event loop then executes the callbacks in the timers queue until the queue is empty or when a maximum number of callbacks is reached. We’ll explore the major phases of the event loop in the sections below.

Like the browser, Node.js has the timers API for scheduling functions that will execute in the future. The timers API in Node.js is similar to that in the browser. However, there are some slight implementation differences.

The timers API consists of the setTimeout, setInterval, and setImmediate functions. All three timers are asynchronous. The timers phase of the event loop is only responsible for handling setTimeout and setInterval.

On the other hand, the check phase is responsible for the setImmediate function. We will explore the check phase later. Both setTimeout and setInterval have the function signature below:

setTimeout(callback[, delay[, ...args]]) setInterval(callback[, delay[, ...args]])

callback is the function to invoke when the timer expiresdelay is the number of milliseconds to wait before invoking callback. It defaults to one millisecondargs are the optional arguments passed to callbackWith setTimeout, callback is invoked once when delay elapses. On the other hand, setInterval schedules callback to run every delay milliseconds.

The diagram below shows the event loop after removing all the phases except the timers phase:

For simplicity, let’s take three scheduled setTimeout that expire concurrently. The steps below describe what happens when the event loop enters the timer phase:

setTimeout callback. If “next ticks” or microtasks are generated while executing the first callback, they are added to their respective queuesetTimeout callback returns, the “next tick” queue is processed. If more “next ticks” are generated while processing the “next tick” queue, they’re added to the back of the “next tick” queue and processed immediately. If microtasks are generated, they are added to the microtask queueIn the steps above, we used a queue of three expired timers. However, that will not always be the case in practice. The event loop will process the timers queue until it is empty or the maximum number of callbacks is reached before moving to the next phase.

The event loop is blocked when executing JavaScript callbacks. If a callback takes long to process, the event loop will wait until it returns. Because Node.js mostly runs on the server side, blocking the event loop will lead to performance issues.

Similarly, the delay argument you pass to the timer functions is not always the exact waiting time before executing the setTimeout or setInterval callback. It is the minimum waiting time. The duration it takes depends on how busy the event loop is, and the system timer used.

During the polling phase, which we will cover shortly, the event loop polls for events such as file and network I/O operations. The event loop processes some of the polled events within the poll phase and defers specific events to the pending phase in the next iteration of the event loop.

In the pending phase, the event loop adds the deferred events to the pending callbacks queue and executes them. Events processed in the pending callbacks phase include certain TCP socket errors emitted by the system. For example, some operating systems defer the handling of the ECONNREFUSED error events to this phase.

The event loop uses the idle, prepare phase for internal housekeeping operations. It doesn’t have a direct effect on the Node.js code you write. Though we won’t explore it in detail, it is necessary to know that it exists.

The poll phase has two functions. The first is to process the events in the poll queue and execute their callbacks. The second function is to determine how long to block the event loop and poll for I/O events.

When the event loop enters the poll phase, it queues pending I/O events and executes them until the queue is empty or a system-dependent limit is reached. In between the execution of the JavaScript callbacks, the “next tick” and microtask queues are drained, like in the other phases.

The difference between the poll phase and other phases is that the event loop will sometimes block the event loop for a duration and poll for I/O events until the timeout elapses, or after reaching the maximum callback limit.

The event loop considers several factors when deciding whether to block the event loop and for how long to block it. Some of these factors include the availability of pending I/O events and the other phases of the event loop, such as the timers phase:

The event loop executes the setImmediate callback in the check phase immediately after I/O events. setImmediate has the function signature below:

setImmediate(callback[, ...args])

callback is the function to invokeargs are optional arguments passed to callbackThe event loop executes multiple setImmediate callbacks in the order in which they are created. In the example below, the event loop will execute the fs.readFile callback in the poll phase because it’s an I/O operation. After that, it executes the setImmediate callbacks immediately in the check phase within the same iteration of the event loop. On the other hand, it processes the setTimeout in the timers phase in the next iteration of the event loop.

When you invoke the setImmediate function from an I/O callback like in the example below, the event loop will guarantee it will run in the check phase within the same iteration of the event loop:

const fs = require("fs");

let counter = 0;

fs.readFile("path/to/file", { encoding: "utf8" }, () => {

console.log(`Inside I/O, counter = ${++counter}`);

setImmediate(() => {

console.log(`setImmediate 1 from I/O callback, counter = ${++counter}`);

});

setTimeout(() => {

console.log(`setTimeout from I/O callback, counter = ${++counter}`);

}, 0);

setImmediate(() => {

console.log(`setImmediate 2 from I/O callback, counter = ${++counter}`);

});

});

Any microtasks and “next ticks” generated from the setImmediate callbacks in the check phase are added to the microtask queue and “next tick” queue respectively and drained immediately like in the other phases.

This close phase is where Node.js executes callbacks to close events and winds down a given event loop iteration. When a socket closes, the event loop will process the close event in this phase. If “next ticks” and microtasks are generated in this phase, they are processed like in the other phases of the event loop.

It is worth emphasizing that you can terminate the event loop at any phase by invoking the process.exit method. The Node.js process will exit, and the event loop will ignore pending asynchronous operations.

As hinted above, it is important to understand the Node.js event loop in order to write performant, non-blocking asynchronous code. Using the asynchronous APIs in Node.js will run your code in parallel, but your JavaScript callback will always run on a single thread.

Therefore, you can unintentionally block the event loop while executing the JavaScript callback. Because Node.js is a server-side language, blocking the event loop will make your server slow and unresponsive, reducing your throughput.

In the example below, I am deliberately running a while loop for about a minute to simulate a long-running operation. When you hit the /blocking endpoint, the event loop will execute the app.get callback in the poll phase of the event loop:

const longRunningOperation = (duration = 1 * 60 * 1000) => {

const start = Date.now();

while (Date.now() - start < duration) {}

};

app.get("/blocking", (req, res) => {

longRunningOperation();

res.send({ message: "blocking route" });

});

app.get("/non-blocking", (req, res) => {

res.send({ message: "non blocking route" });

});

Because the callback is executing a time-consuming operation, the event loop is blocked for the duration the task is running. Any request to the /non-blocking route will also wait for the event loop to first unblock. As a result, your application will become unresponsive. Your requests from the frontend will become slow and eventually timeout. To perform such CPU-intensive operations, you can take advantage of the worker thread.

Similarly, do not use the synchronous APIs for the following modules on the server side because they can potentially block the event loop:

cryptozlibfschild_processAs explained above, Node.js runs JavaScript code in a single thread. However, it has worker threads for concurrency. To be precise, in addition to the main thread, Node has a thread pool comprised of four threads by default.

Libuv, the C library that gives Node.js its asynchronous, non-blocking I/O capability is responsible for managing the thread pool. Node.js gives you the capability of using additional threads for computationally expensive and long-lasting operations to avoid blocking the event loop.

Node promises do not run on a separate thread. The .then, .catch, and .finally callbacks are added to the microtask queue. As explained above, the callbacks in the microtask queue are executed on the same thread in all the major phases of the event loop.

The event loop orchestrates the asynchronous and non-blocking feature of Node. It is responsible for monitoring client requests and responding to requests on the server side.

If a JavaScript callback blocks the event loop, your server will become slow and unresponsive to client requests. Without the event loop, Node.js would not be as powerful as it is now, and Node.js servers would be painfully slow.

Node.js has several built-in synchronous and asynchronous APIs. Synchronous APIs block the execution of JavaScript code until the operation is complete.

In the example below, we’re using fs.readFileSync to read file contents. fs.readFileSync is synchronous. Therefore, it will block the execution of the rest of the JavaScript code until the file reading process is complete before moving to the next line of code:

const fs = require("fs");

const path = require("path");

console.log("At the top");

try {

const data = fs.readFileSync(path.join(__dirname, "notes.txt"), {

encoding: "utf8",

});

console.log(data);

} catch (error) {

console.error(error);

}

console.log("At the bottom");

On the other hand, non-blocking asynchronous APIs perform the operations in parallel by offloading them to the thread pool or the native system on which Node.js is running. When the operation is complete, the event loop schedules and executes the JavaScript callback.

For example, the async form of the fs module uses the thread pool to write or read file contents. When the contents of the file operation are ready for processing, the event loop executes the JavaScript callback in the poll phase.

In the example below, fs.readFile is async and non-blocking. The event loop will execute the callback you pass to it when the file read operation is complete. The rest of the code will run without waiting for the file operation to complete:

const fs = require("fs");

console.log("At the top");

fs.readFile("path/to/file", { encoding: "utf8" }, (err, data) => {

if (err) {

console.error("error", err);

return;

}

console.log("data", data);

});

console.log("At the bottom");

Microtasks are executed between operations in all the major phases of the event loop. Each major phase of the event loop executes a queue of JavaScript callbacks. Between executions of successive JavaScript callbacks in the phase queue, there is a microtask checkpoint where the microtask queue is drained.

The Node.js event loop runs for as long as there are pending events for it to process. If there isn’t any pending work, the event loop exits after emitting the exit event, and the exit listener callback returns.

You can also exit the event loop by explicitly using the process.exit method. Invoking process.exit will immediately exit the running Node.js process. Any pending or scheduled events in the event loop will be abandoned:

process.on("exit", (code) => {

console.log(`Exiting with exit code: ${code}`);

});

process.exit(1);

You can listen for the exit event. However, your listener function must be synchronous because the Node.js process will exit immediately after the listener function returns.

The Node runtime environment has APIs to write non-blocking code. However, because all your JavaScript code executes on a single thread, it is possible to block the event loop unintentionally. An in-depth knowledge of the event loop helps you write robust, secure, and performant code and effectively debug performance issues.

The event loop has about six major phases. These six phases are the timers, pending, idle and prepare, poll, check, and close. Each phase has a queue of events that the event loop processes until it is empty or reaches a hard system-dependent limit.

While executing a callback, the event loop is blocked. Therefore, be sure your asynchronous callbacks don’t block the event loop for long, otherwise your server will become slow and unresponsive to client requests. You can use the thread pool to perform long-running or CPU-intensive tasks.

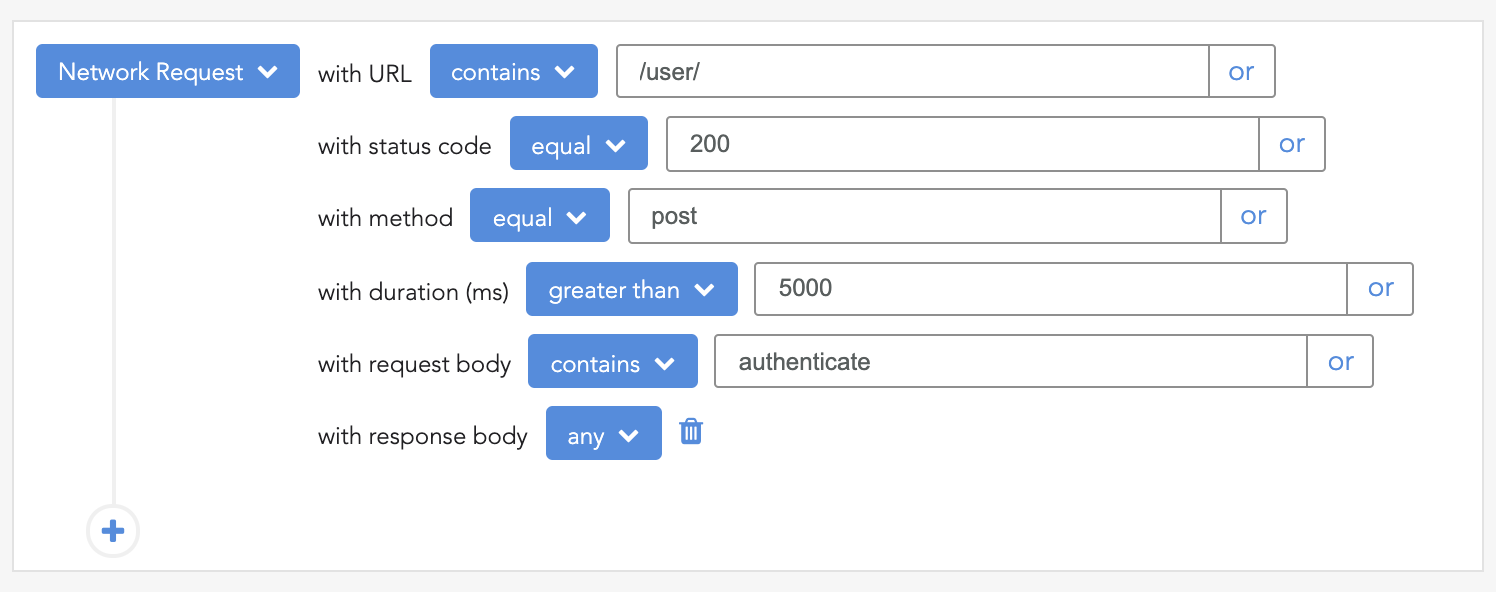

Monitor failed and slow network requests in production

Monitor failed and slow network requests in productionDeploying a Node-based web app or website is the easy part. Making sure your Node instance continues to serve resources to your app is where things get tougher. If you’re interested in ensuring requests to the backend or third-party services are successful, try LogRocket.

LogRocket lets you replay user sessions, eliminating guesswork around why bugs happen by showing exactly what users experienced. It captures console logs, errors, network requests, and pixel-perfect DOM recordings — compatible with all frameworks.

LogRocket's Galileo AI watches sessions for you, instantly identifying and explaining user struggles with automated monitoring of your entire product experience.

LogRocket instruments your app to record baseline performance timings such as page load time, time to first byte, slow network requests, and also logs Redux, NgRx, and Vuex actions/state. Start monitoring for free.

Signal Forms in Angular 21 replace FormGroup pain and ControlValueAccessor complexity with a cleaner, reactive model built on signals.

Discover what’s new in The Replay, LogRocket’s newsletter for dev and engineering leaders, in the February 25th issue.

Explore how the Universal Commerce Protocol (UCP) allows AI agents to connect with merchants, handle checkout sessions, and securely process payments in real-world e-commerce flows.

React Server Components and the Next.js App Router enable streaming and smaller client bundles, but only when used correctly. This article explores six common mistakes that block streaming, bloat hydration, and create stale UI in production.

Hey there, want to help make our blog better?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now

One Reply to "A complete guide to the Node.js event loop"

Nice blog. Worth reading.